Multiple calls across social media requesting the UK to withdraw from the ECHR. Why now?

And what are the possible Legal, Social, and Political Consequences of Departure

Pre Amble

This is a really long article, and I apologise in advance for that, but it touches on big issues. However, before launching into the weeds of the same I wish to make something unequivocally clear. I do not believe that human rights—those fundamental, inviolable principles that define our dignity—should be granted by any state or supranational authority. Rights, by definition, are not gifts. They are not privileges. They are ours by virtue of our humanity. The idea that some distant bureaucracy or self-interested government bestows upon us the right to think, to speak, to live freely, is not only laughable but also insulting. We are born equal in our humanity. As such, no border, no law, no institution has the moral authority to declare otherwise.

A further deeply unsettling outcome of having rights issued to us, is the fact that some of those rights can be “qualified”. The moment a government reserves for itself the power to decide when and how a right applies, it stops being a right and becomes a conditional favour. And conditional favours are the language of domination, not freedom.

This is exactly the position with the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and the Human Rights Act 1998 (HRA) in the UK, and I do recognise this. While they purport to enshrine our rights in law, they simultaneously allow for qualification or derogation—times when the state can opt out—as if our dignity is a contractual clause.

I believe human rights should be jus cogens norms: absolute, unbreakable, and non-negotiable. But this is not the world we live in and anyone pretending that it is, is lying to themselves. We instead exist in a system that mimics servitude, where those in power define what our freedom looks like—and quietly reserve the right to take it away. Until this changes, until we change that, it is as it is.

So even with the conviction stated above burning within me, I must be pragmatic. And so must you. In today’s volatile political climate, rejecting even the watered-down protections offered by the ECHR and HRA would be a dangerous act of idealism—because in doing so, we will be tacitly agreeing to having nothing at all in the way of codified rights. We will surrender tools that, imperfect as they are, still offer some critical leverage in resisting deeper authoritarianism.

Take Article 8: the right to respect for private and family life. In an age where mandatory digital ID schemes loom like a techno-authoritarian spectre, clinging to even the imperfect shield of Article 8 has become a strategic necessity for now. Therefore, to abandon such protections would be more than naïve—it would be suicidal in the fight for our privacy, autonomy, and fundamental humanity.

So, as you read what follows, bear in mind this tension: I reject the premise of rights being granted, but I also refuse to be so purist that I walk willingly into the jaws of further servitude in the current political climate.

Introduction

Intuition often serves as a compass, subtly guiding decisions before the rational mind has fully mapped a terrain. When it comes to the legal protections enshrined in the ECHR, I instinctively sense that relinquishing such safeguards now by withdrawing from the convention, would constitute a significant strategic blunder, especially give how politically uncertain and volatile things are in the UK at this time.

The ECHR is heralded as one of the cornerstones of post-war European cooperation and jurisprudence. Drafted in 1950, in the shadow of the atrocities of the Second World War, the Convention was designed to set a baseline of fundamental rights and freedoms for all signatory states, and to establish a supranational judicial mechanism—the European Court of Human Rights—to enforce those rights. The United Kingdom was not only a founding signatory but played a pivotal role in the drafting of the ECHR and in promoting human rights as a European norm.

While I’ve already addressed the fact that some of the rights under the ECHR (and indeed the HRA), may be qualified or limited in certain contexts, and have acknowledged the imperfections of both the ECHR and the HRA, my main focus in writing this article is to highlight the intensifying political momentum—particularly in the past six months—behind calls for the UK’s withdrawal from the ECHR.

These efforts are largely framed as a remedy to illegal immigration, specifically the “small boats problem,” and as a response to perceived misapplications of the ECHR in immigration-related cases. Yet what’s striking is how such proposals circulate widely—especially on social media—without confronting the complexities of the issue of legal and illegal migration in the UK and moreover without discussing the profound and far-reaching consequences that withdrawal from the ECHR would entail.

There is no discourse on the legal uncertainty and constitutional disruption withdrawal would unleash. And I am troubled by the lack of recognition that withdrawal would pose, to rights protections that extend to all citizens, not just immigrants. The silence around these implications is troubling—perhaps a symptom of the broader oversimplification of complex topics in favour of emotionally charged political and social media debates.

Social Media demands withdrawal from the ECHR

As noted above, the recent calls to leave the ECHR seem to centre solely around the issue of illegal immigration. Angered by what they perceive as unfettered small boat arrivals, coupled with an inability to deport migrants, especially those that have committed crimes, people are furiously, and of their own volition, calling for departure from the ECHR as a mechanism to deal with the same.

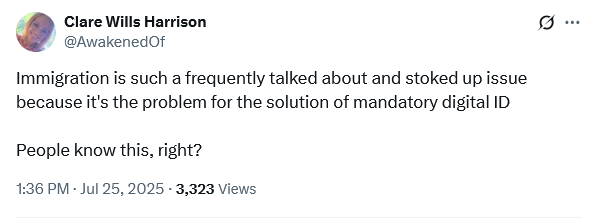

I can’t help but think that there is an issue here with consent to removal of one’s own rights. For all its faults, the ECHR does grant significant, (albeit qualified), rights to private and family life that would be particularly helpful in dealing with the issue of mandatory digital ID. So, it seems strange that just as the imposition of the same is back on the table, there is at the exact same time a repeated call for withdrawal from the ECHR from the “usual quarters”.

For instance, Rupert Lowe has repeatedly posted on X that he feels we should simply withdraw from the ECHR, presumably because he believes this would solve all our immigration problems. It obviously would not, and in fact we could of course solve a lot of them without leaving the ECHR at all. Lowe’s posts are largely supported and echoed by what I regard as the usual suspects in pushing agendas. Some of those involved are those that Sonia Poulton mentions in her video here and more particularly Matt Goodwin, and of course fanatical Zionist’s Suella Braverman and Kemi Badenoch. There are also some less obvious pushers, like Adam Brooks, June Slater, and something called The British Patriot on X (which I think is a Zionist run account). There are also many naive Reform supporters and other regular people, that perhaps do not fully understand the implications of what they are saying and likely do not know very much about our legal system or our constitution, parroting the same message gleefully. What none of those posting the withdrawal request ever discuss, are the political and legal ramifications that might arise in the UK if we withdraw from the ECHR now. And neither do they point out that such withdrawal will affect the whole of UK society, not just immigrants, illegal or otherwise. Given this, it is hard not to view the repeated daily calls for the UK to withdraw from the ECHR as a strategy being employed to lead to somewhere – problem, reaction, solution style.

Anyone that follows our Telegram channel will know that I, and the other admins that post on the channel, believe the immigration issues we are experiencing are purposeful and allowed, and further that immigration - particularly illegal immigration - is being used as a mechanism not only to enforce further restrictions on protests and free speech, but also to promote digital ID as a solution. Given this, it is worrying that all those fired up by illegal immigration are calling for withdrawal from the ECHR without considering the wide ramifications on the whole of the UK public as regards loss of Article 8 rights, which would particularly apply to push backs against digital ID. I cover this aspect below in more detail, but before we get there let’s explore some immigration figures as well as the ECHR immigration arguments that I have seen posted on social media by the aforementioned usual suspects.

Immigration figures

Illegal Immigration

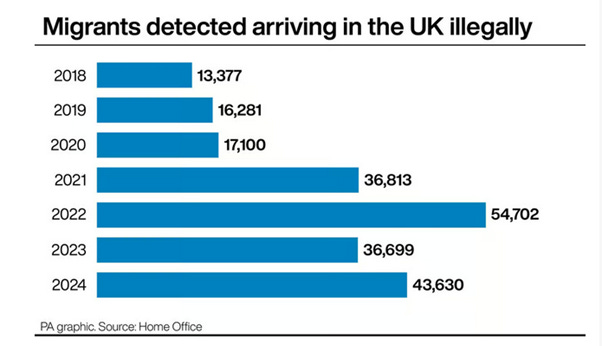

In 2024, the UK recorded approximately 43,630 detected illegal arrivals, according to Home Office data. This marked a 19% increase compared to 2023, when 36,699 were detected.

Here’s a breakdown of how they arrived:

84% came via small boats across the English Channel.

The rest arrived by air (8%), at UK ports (1%), or were detected within 72 hours of arrival (7%).

The most common nationalities among these arrivals included:

Afghanistan (6,339 people)

Iran (5,370)

Syria (4,945)

Eritrea (3,920)

Vietnam (3,798)

It’s important to note that these figures only reflect detected arrivals. The actual number of people living in the UK without legal status is unknown, as many remain undetected

Graph taken from https://www.standard.co.uk/news/politics/illegal-migrants-uk-nationalities-home-office-b1219785.html

To end of May 2025, the United Kingdom saw about 14,800 people arrive by small boats, a 42% jump compared to the same period in 2024. According to the linked article, by late April, the number of small boat crossings had already passed 10,000—over a month earlier than the previous year.

The majority of arrivals are adult men (76%), with children under 18 making up around 14%.

Afghans are the largest nationality group so far in 2025, accounting for 16% of small boat arrivals. Please note that the covert Afghan resettlement operation following the data breach, is not related in any way to small boat arrivals, as the former are obviously considered legal migrants under the scheme.

Broader Illegal Migration Trends

Between 2018 to date, the UK recorded 175,000 unauthorised arrivals, with 78% arriving by small boat.

In 2025 to date, the UK saw over 23,000 small boat arrivals by mid-year.

The asylum backlog remains high, with nearly 30,000 small boat arrivals still awaiting initial decisions as of March 2025.

Returns and Deportations

Between 5 July 2024 and 22 March 2025, the UK carried out 24,103 returns, including:

6,339 enforced returns of people with no legal right to remain.

3,594 foreign national offender (FNO) returns.

6,781 asylum-related returns.

Legal Immigration

Legal immigration in 2024

Total long-term immigration: According to the ONS, approximately 948,000 people came to the UK intending to stay at least a year.

Emigration: Around 513,000 people left the UK.

Net migration: Estimated at 435,000, down from 906,000 in 2023 — the sharpest annual drop on record.

Visa Breakdown (2024)

Visa Type Number Granted

Work visas 210,000

Study visas 393,000

Family visas 86,000

Humanitarian routes 79,000

Settlement grants 162,000

Citizenship grants 270,000

Legal migration data for the full year of 2025 is obviously not yet available, but what you will glean from the 2024 figures is that illegal immigration is a drop in the ocean when compared to legal migration. Further, study visas make up nearly half of all visas granted in 2024. There is a reason for this. The legal migration study visa route—primarily through international students—is massively valuable to UK universities, both financially and strategically. International students typically pay 2–3 times more than domestic students for university fees. In 2021-22, over £9 billion was generated from international tuition fees alone. Many universities rely on international fees to subsidise domestic teaching and research, especially as government funding has stagnated, so you can imagine that they lobby rather hard for study visas to remain as high as they are. Further, international students contribute an estimated £37 billion annually to the UK economy when factoring in accommodation, food, transport, and other spending.

UK universities, primarily through representative bodies like Universities UK (UUK), engage in significant lobbying efforts to maintain high levels of study visas and protect the international student market, which they see as critical to their financial stability. UUK represents over 140 UK universities and also conducts surveys to highlight what they call “the impact of visa restrictions”, such as a 2025 survey showing a 33% drop in study visas and a 40% decline in postgraduate enrolments since January 2024 policy changes. These findings are used to argue against further restrictions, stressing economic damage to universities and local economies.

Universities also leverage connections with MPs who have university constituencies, to influence policy. For instance, lobbying efforts target education and trade committees to emphasise the benefits of international students to the UK economy and global reputation.

UUK and individual universities might also provide evidence to government consultations, such as the Migration Advisory Committee (MAC) review, and advocate for maintaining the Graduate Route visa, which allows international students to stay and work in the UK post-graduation.

Universities also work with education consultancies and recruitment agencies to align messaging, emphasising the need for flexible visa policies to attract students who might otherwise choose competitors like the US, Canada, or Australia.

The lobbying picture is the same as regards work visas, the next highest number of visas granted after study visas. The visa figure includes Skilled Worker, Health and Care Worker, and other work-related visa categories. It will therefore come as no surprise that the NHS Confederation, Care England, and the National Care Forum are key players advocating for sustained access to work visas, particularly the Health and Care Worker Visa, and have lobbied to retain the same, emphasising the sector’s reliance on international workers to address chronic staffing shortages.

However, TechUK and creative industry bodies like the Creative Industries Council also advocate for flexible visa policies to attract “global talent” and the former has lobbied for streamlining endorsement processes. Further, the Construction Industry Council (CIC) and the Confederation of British Industry (CBI) likewise represent these sectors’ interests. The CIC lobbied for construction roles like structural welders and logistics managers to be included on the Temporary Shortage List, allowing temporary sponsorship for RQF 3-5 roles critical to infrastructure projects. This was in response to the 2025 rule changes removing 180 mid-skilled occupations from eligibility. The CBI has worked with the Department for Business and Trade to develop workforce plans, as required by the MAC, to justify continued visa access for roles facing domestic shortages. They argue that construction contributes £117 billion annually to the UK economy, necessitating international workers to meet demand.

UKHospitality and the British Retail Consortium (BRC) advocate for these sectors, which rely heavily on mid-skilled migrant labour. UKHospitality has lobbied to retain access to Skilled Worker visas for roles like chefs and retail managers, arguing that domestic recruitment cannot meet demand due to low wages and high turnover. They cited a 2024 survey showing 60% of hospitality businesses faced recruitment challenges.

As you can see, across sectors industry bodies submit evidence to the MAC, which advises the Home Office on visa policies, and hence there is a sophisticated lobbying ecosystem where industries, particularly private businesses, advocate for visa policies that align with their economic interests, often more aggressively than sectors like healthcare, which have a public service angle. Simply put, private industries drive a complex, self-interested lobbying machine to keep work visas high, often prioritising profit over broader systemic fixes like upskilling locals, and of course the argument against this is that it suppresses wages and disincentivises domestic training.

All of the above is to point out that Rupert Lowe constantly posting “let’s leave the ECHR to solve our immigration problems” is disingenuous, ill-informed, and indicative that he does not really understand what is happening as regards the immigration landscape, because he constantly places his focus on illegal immigration being the only problem in the UK where immigration is concerned. Indeed, the rhetoric around the latter has got consistently worse over the last year or two, with frequent scaremongering posts from many social media accounts saying things like “UK being taken over by Islamists”, “UK being invaded” or as a variation “The native population of the UK will soon cease to exist”. There are many more adaptations of these posts across social media and invariably most focus the immigration issue and any problems arising from it, as being about illegal immigration only. It feels very much like the “Covid” era scaremongering propaganda at times.

We can see from what I have said above that legal immigration also plays a large role in changing demographics and changing culture in towns and cities. The issue is not exclusively related to yearly illegal migration which makes up only a very small portion of the total yearly immigration figures– around 5% based on 2024 data. Having said this, a search of Hansard reveals that on 7th May 2024 Andrea Jenkyns stated that “The most recent robust estimates of the size of the unauthorised resident population in the UK put it at around 400,000-600,000 in the early 2000s…More recent but less robust estimates have put the population at between 800,000 and 1.2 million in 2017…It is likely none of these estimates accurately captures the situation in 2024.” Jenkyns also touched on the associated costs of the same to the UK public saying “Even the most basic calculations put the economic burden on the British taxpayer of an illegal migration population of 1.2 million at £14.4 billion”.

If what Jenkyns stated is true, we clearly do have a problem with illegal immigration that is unsustainable, and I am not denying that. What I am saying, however, is that it has been allowed to happen on purpose and now it is being used to lead people to a solution. But not a solution that the people want, one that the parasitic class want.

ECHR Withdrawal Arguments on Social Media

One of the most frequently cited arguments in favour of withdrawal from the ECHR is the restoration of sovereignty and democratic accountability. The current system allows an international court—the ECtHR—to overrule decisions made by UK courts and Parliament, especially in immigration matters. Critics argue that this undermines the UK’s ability to tailor its immigration rules to reflect the priorities and concerns of its own electorate. Those arguing for withdrawal posit that without the constraint of the ECHR, the UK could enact immigration laws and enforce deportation decisions about illegal immigrants or those on visas that’s have committed crimes, without the risk of these being stalled or overturned by appeal to Strasbourg. They therefore believe this would enable a more streamlined and politically responsive immigration system, where Parliament’s decisions are final. This is because persistent and often valid criticisms of the ECHR from an immigration perspective concern Article 3 (prohibition of torture, inhuman or degrading treatment) and Article 8 (right to private and family life). These articles have been cited in numerous cases as reasons why foreign nationals, including individuals convicted of serious crimes or suspected of terrorism, cannot be deported if significant risk exists in their home country.

Those advocating for withdrawal from the ECHR believe the same would, in theory, allow the UK to bypass such legal barriers and presumably those advocating for withdrawal also believe the government would then prioritise public safety and national security over individual rights in more cases, permitting the removal of foreign criminals and suspects who currently remain in the UK because of ECHR protections. Withdrawal is therefore sold as a means of reinforcing the integrity of the immigration system and maintaining public confidence.

The ECHR’s protections do, of course, extend to those seeking asylum, mandating, for instance, that individuals cannot be returned to countries where they face a real risk of torture or ill-treatment. While this principle aligns with other international agreements (such as the UN Refugee Convention), the ECtHR’s expansive interpretation can constrain government policy. Proponents of withdrawal therefore argue that it would grant the UK greater latitude to reshape its own asylum process, potentially introducing more rigorous requirements, expedited procedures, or alternative arrangements for assessing claims. They believe that withdrawal from the ECHR would allow the government to respond nimbly to emerging immigration pressures and crises without the risk of Strasbourg-imposed legal delays.

In summary, those who advocate for the UK's withdrawal from the ECHR view it as a chance to reclaim control over national immigration policy. They argue that such a move would empower the government to protect the public, streamline immigration processes, and restore trust in a system they see as convoluted and compromised by external oversight. Yet this argument, compelling on the surface, crumbles under closer scrutiny.

It crumbles because it does not take account of the legal migration that would continue post any withdrawal. The ECHR does not factor in any of the legal migration cases, (unless those with lawful status (e.g. visa holders, refugees, settled migrants) are facing deportation as they have been convicted of serious crimes), so legal migration would remain as high, if not get higher, than it currently is post any withdrawal from the ECHR. The argument also crumbles because it hinges on the belief that withdrawal from the ECHR is the sole mechanism by which illegal immigration concerns can be dealt with. The argument crumbles entirely when you realise it relies on a false confidence that UK governance is genuinely independent of global and corporate influence — that our political parties are distinct entities working solely for the good of citizens, and that Strasbourg alone is the obstacle to effective illegal immigration control. This vision relies on denying what has become increasingly evident: the UK’s political landscape is not a contest of competing ideologies but a uni-party system beholden to supranational agendas and corporate interests. The continuity in policies covering all aspects of our lives— from pandemic-era mandates across party lines, to today's legislation on surveillance, digital ID, AI oversight, and police powers — reveals a UK political system that is in lockstep, not in healthy democratic competition. And it ignores the supranational forces at play in this lockstep as regards immigration, such as the UN, and particularly their study “Replacement Migration: Is it A Solution to Declining and Ageing Populations?, which can be found here.

It is therefore most confusing to me when those who rightly criticised the “Covid” response, seeing through the coordinated global narrative and the erosion of civil liberties arising from the same, now appear to place sudden faith in this same system to deliver principled immigration reform if we can only all be freed from the ECHR, which would of course, mean ALL OF US giving up our rights enshrined therein. For some unknown reason the people espousing this also believe that following withdrawal from the ECHR, the government that they are consistently moaning about as failing on all sorts on issues, including immigration, would happily grant us all some shiny new rights to protect us from their overreach. It boggles the mind and this contradiction is striking. The same citizens who decried the loss of rights under emergency powers in 2020 and 2021, now propose a further erosion of rights for all citizens to solve a single, complex issue. They are demanding that everyone in the UK forfeit ECHR and HRA protections to deal with the immigration issue, (which by all accounts seems to be a centralised supra national policy, and certainly a policy supported by private business lobby groups), thereby repeating the collective punishment logic that many of them very likely took to the streets to oppose during 2020 and 2021. They took to the streets because they realised that freedom for all cannot be selectively traded in pursuit of narrower policy goals. Now they have forgotten this lesson and believe that the state is not tempted to act without constraint on any matter, including using illegal immigration to reduce all citizens rights further. How foolish.

Legal Consequences

The ECHR acts as a shield for individuals against abuses and overreach by the state. It does not always work and certainly rights are sometimes not upheld - as they are seen fit to be qualified for some reason or other - so I am not claiming it is perfect. However, the rights enshrined in the Convention—such as the right to a fair trial, prohibition of torture, freedom of expression, and respect for private and family life—are deeply woven into the fabric of UK law. Withdrawing from the ECHR would inevitably weaken these protections.

The Human Rights Act 1998, (the HRA), which incorporates the ECHR into domestic law, would likely have to be repealed or extensively amended if the UK withdrew from the ECHR. This would create a legal vacuum, and individuals would lose the ability to challenge government actions in both British courts and, crucially, at the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg. And anyone who thinks that the government would grant enshrined new rights following UK withdrawal from the ECHR is living in a fantasy land. Look back at the last 5 years for proof. No government in the UK is interested in broadening rights, it’s all about removing rights or restricting them, and this can be seen from all the rights restricting legislation coming onto our statute books, (check out my “Legislation Watch” articles for more on this).

The HRA and ECHR are interlinked as the HRA incorporates the rights from the ECHR directly into UK law. It requires UK courts to interpret legislation in line with ECHR rights and allows individuals to bring human rights claims in domestic courts. The HRA also obliges public authorities to act compatibly with ECHR rights. So, if the UK were no longer a signatory to the ECHR, the HRA would become legally incoherent, as it references a treaty the UK would no longer adhere to.

Some proposals suggest replacing the HRA with a British Bill of Rights, but unless it replicated ECHR rights and enforcement mechanisms, it would mark a major shift in how rights are protected.

Further, the ECHR is embedded in multiple layers of the UK’s legal system, influencing not only the courts but legislation, government policy, and devolved governance. Withdrawal would require an immense and complex legal disentanglement, affecting countless statutes and precedents that rely on Convention rights. The resulting uncertainty could generate a period of constitutional upheaval and protracted danger for state overreach leading to litigation, and unjust rules and requirements, as we grapple with a new legal order and the unresolved status of rights protections.

Quite simply, does anyone, seriously have faith in any government of this country to give us greater protections if we withdraw from the ECHR, after EVERYTHING that has happened over the last 5 years?

ECHR verses other legal protections

Another argument that I regularly see on social media when challenging the withdrawal from the ECHR is that our common law and statute between them offer all the protections of the ECHR. This is simply not true. Below I have set out a comparative analysis as regards Article 8 ECHR. I have used this Article as it relates to my comments on mandatory digital ID which follow below.

1 Breadth of Protection

Article 8 (ECHR): Covers a wide spectrum, including privacy, family life, sexual orientation, home, correspondence, personal autonomy, and the state’s positive obligations to protect individuals even from non-state actors. Its interpretation evolves through jurisprudence, adapting to new realities such as digital privacy.

Common Law: Historically, the UK common law has recognised certain privacy interests (such as the tort of breach of confidence and, more recently, misuse of private information). However, it has developed incrementally and often focuses on protection from private parties rather than the state. There is no comprehensive or codified right to privacy, and protection for family life, home, and correspondence, is scattered and often incomplete.

Statutory Protections: Several statutes touch on related rights, such as the Data Protection Act 2018 (implementing GDPR), the Investigatory Powers Act 2016, and child protection statutes. Yet, these laws tend to be specific in scope and lack the overarching, flexible, and principle-based approach that Article 8 provides. They do not amount to a broad constitutional right to privacy and family life.

2 Enforceability and Remedies

Article 8: Through the Human Rights Act 1998, individuals can directly invoke Article 8 before UK courts. Courts are obliged to interpret legislation, as far as possible, in a way compatible with Article 8. There is also the ultimate right to petition the European Court of Human Rights.

Common Law & Statute: Remedies are limited to the causes of action available—such as damages for misuse of private information or judicial review of public body decisions. The scope of judicial review is more restricted, very expensive, and not all invasions of privacy or family life are actionable. Statutory remedies are only available within the narrow confines of each law’s subject matter.

3 Scope of State Obligations

Article 8: Imposes both negative obligations (not to interfere arbitrarily) and positive obligations (to take active steps to secure respect for private and family life, even when threatened by others).

Common Law & Statute: Common law rarely imposes positive obligations on public bodies to act to secure privacy or family life. Statutory duties are again specific and piecemeal, rather than comprehensive.

Why the Above Matters: Strategic Consequences

The absence of Article 8’s broad, principle-based framework in common law or statute presents key risks:

Patchwork Protection: Rights are not guaranteed comprehensively. Some individuals may fall through the cracks or be left without remedy depending on the nature of the intrusion or the actor involved.

Reduced Flexibility: Article 8’s general language allows courts to respond to novel threats (e.g., new technology, surveillance). Statutory and common law approaches are much slower to adapt.

Vulnerability of the Marginalised: Those most at risk—such as children, minorities, or those facing state power (all of us!)—may find themselves without robust legal tools to protect their rights.

In short, the protections of Article 8 are broader, deeper and more adaptable than those cuurently available under UK common law or statute. To lose them would be to accept a legal framework that is less certain, less comprehensive, and less capable of safeguarding rights in a rapidly changing world.

Historical and contemporary examples indicate that erosion of privacy rights often precipitate broader civil discontent, particularly when individuals feel exposed or unsafe from state overreach. Once trust is lost, it is exceedingly difficult to restore, as the stability of democratic societies is fundamentally tethered to this trust. To lose Article 8 protections at this particularly volatile political time would not merely be a technical or administrative change. It would represent a seismic shift in the balance between state power and individual rights, with ramifications extending far beyond the legal sphere. If we draw on the lessons of history and the quiet knowledge of what makes societies strong, we see warnings that such a move would almost certainly be a strategic mistake—one that invites instability, undermines trust, and exposes the vulnerable at precisely the moment when resilience and cohesion are most needed.

Social and Political Consequences

While advocates of withdrawal often argue that “British rights” could replace Convention rights, there is no guarantee that domestic alternatives would offer the same breadth or strength of protection. The ECHR is interpreted as a living instrument, evolving with changing social norms; a purely national rights regime would be more vulnerable to internal political pressures and the whims of the government of the day. Vulnerable individuals and minority groups would be especially at risk if rights protections were diluted.

The ECHR is not a foreign imposition but a framework in which the UK has long played a formative part. Withdrawal could further erode public trust in the country’s commitment to justice, fairness, and the rule of law, and it would send a definite signal of a retreat from values that have shaped modern Britain’s identity and international reputation.

Ironically, withdrawal from the ECHR might also not reduce the volume of rights-based litigation, but instead increase it. Without the clarity and authority provided by the Convention and the Strasbourg Court, individuals and groups would likely challenge any new regime, leading to protracted legal disputes and a lack of legal certainty.

Article 8 arguments against mandatory digital identity - aka Britcard

I believe that the strongest legal argument against mandatory digital ID in the UK currently centres on Article 8 of the ECHR, incorporated into UK law via the HRA, which guarantees the right to respect for private and family life, albeit a qualified right so the state can interfere with or limit the same. However, they can only do this if the interference is:

In accordance with the law

Necessary in a democratic society

Pursuing a legitimate aim, such as:

National security

Public safety

Economic well-being

Prevention of disorder or crime

Protection of health or morals

Protection of the rights and freedoms of others

I believe one of the many things that illegal immigration serves is to embolden the government to call for mandatory digital ID for “national security” measures. This is why I say that the immigration mess is purposeful - it serves a long desired goal of enforced identity documents for all UK citizens. When you look at patterns, calls for UK withdrawal from ECHR at same time as weakening of jury trials, further intrusive surveillance, anti protest and anti free speech legislation coming through, the calls seems very much part of a commitment to the overall stripping of liberties of all UK residents, and this is the real danger that we face.

Notwithstanding any national security calls, the legal argument against mandatory digital ID via Article 8 is particularly potent due to the potential for mandatory digital ID systems to disproportionately interfere with privacy through mass data collection, surveillance, and profiling. Below, I outline this primary argument, and compare what statutory rights and common law rights one might have as regards mandatory digital ID if the UK withdrew from the ECHR.

Using Article 8 ECHR against mandatory digital ID

Art 8 provides robust protection against unwarranted state intrusion into private life, requiring any interference to be in accordance with the law, pursue a legitimate aim, and be necessary and proportionate. A mandatory digital ID system could violate Article 8 by:

Excessive Data Collection: Requiring citizens to provide sensitive personal data (e.g., biometrics) for a digital ID could constitute an unjustified intrusion, especially if the data is stored centrally or shared with third parties without clear consent.

Surveillance and Profiling Risks: Digital ID systems, particularly those linked to multiple services, could enable tracking of individuals’ activities, leading to unwarranted surveillance or behavioural profiling.

Lack of Proportionality: The blanket imposition of digital IDs is unlikely the least intrusive means to achieve aims like fraud prevention, national secutiry, or immigration control, especially if less invasive alternatives (e.g., voluntary IDs or paper-based systems) are viable.

Erosion of Autonomy: Forcing individuals to use a digital ID to access essential services (e.g., work, housing, or voting) could undermine personal autonomy and freedom, particularly for those who lack digital access or skills.

Legal Test: For a mandatory digital ID to comply with Article 8, it must:

Be based on clear, accessible, and foreseeable domestic law (legality).

Serve a legitimate aim (e.g., national security, public safety, or fraud prevention).

Be necessary and proportionate, meaning the benefits must outweigh the privacy intrusion and no less intrusive alternative exists.

S. and Marper v. UK (2008) — The Court ruled that indefinite retention of DNA profiles and fingerprints of individuals not convicted of any crime was a disproportionate interference with their right to privacy. It criticised the blanket and indiscriminate nature of the UK’s policy, which failed to consider the gravity of the offence, the age of the suspect and the lack of time limits or review mechanisms. The ECtHR stressed that modern biometric technologies require careful balancing of public safety and private life, especially when used on innocent individuals.

Gaughran v. UK (2020) —The Court found that indefinite retention of biometric data and photographs of a man convicted of a minor offence (drink driving) also violated Article 8. It emphasised the lack of safeguards or meaningful review, the absence of proportionality in retaining data regardless of offence severity and the risk of arbitrariness, especially with evolving technologies like facial recognition. The Court warned that accepting the logic of “more data equals more security” could justify mass surveillance, which it deemed excessive and irrelevant.

Why Article 8 Outweighs Other Arguments:

International Law Binding: The ECHR is binding on the UK under the HRA, and courts have consistently upheld Article 8 in privacy-related cases.

Broad Scope: It covers not just data collection but also the broader implications of surveillance and loss of control over personal identity.

Judicial Precedent: Cases like those above show courts are willing to strike down measures that disproportionately infringe privacy.

Compared to common law (less specific to privacy) or statutory rights (often narrower), Article 8’s human rights framework offers a more comprehensive challenge.

Other challenges may be available under the ECHR and other international law, but I do not feel they contain the strongest legal arguments against mandatory digital ID.

Statutory Rights (UK Legislation) and Common Law that might apply if the UK withdrew from the ECHR

Data Protection Act 2018 (DPA) and GDPR

Data Protection Rights which governs personal data processing, requiring lawfulness, fairness, transparency, and data minimisation.

Mandatory digital IDs could breach GDPR principles if they collect excessive data, lack clear consent, or fail to protect data adequately (e.g., centralised databases prone to breaches). The Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) could enforce penalties.

Strength: Specific and enforceable by the ICO; aligns with Article 8.

Limitation: Government could claim exemptions for public interest or legal obligations.

Equality Act 2010 – Anti-Discrimination

Prohibits discrimination based on protected characteristics (e.g., age, disability, race) in accessing services.

A mandatory digital ID could indirectly discriminate by excluding groups with limited digital access (e.g., elderly or low-income individuals), violating access to services like housing or employment.

Strength: Strong for addressing social exclusion and inequity.

Limitation: Requires evidence of disproportionate impact on specific groups.

Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA)

Grants public access to information held by public authorities.

Could be used to demand transparency about digital ID system operations, data sharing, or security measures, exposing potential flaws.

Strength: Supports public accountability.

Limitation: Limited to transparency; does not directly challenge the system’s legality.

Common Law Rights

Right to Privacy - English common law does not recognise a general right to privacy (no standalone tort of privacy). Instead, it offers piecemeal protection through:

Breach of confidence (e.g. misuse of private information)

Trespass and nuisance (protecting physical privacy)

Defamation and harassment laws

Through emerging common law principles UK courts have occasionally recognised a limited common law right to privacy, evolving from cases like Campbell v. MGN Ltd [2004].

Could therefore be argued that mandatory digital IDs infringe on a reasonable expectation of privacy, especially if data is misused or overly intrusive.

Strength: Supplements Article 8 in the absence of HRA/ECHR.

Limitation: Less developed than ECHR protections and not as robust; courts may defer to statutory frameworks.

Judicial Review – Ultra Vires or Unreasonableness

Common law allows courts to review government actions for legality, rationality, or procedural fairness

Could challenge the enabling legislation or administrative actions for digital IDs as exceeding statutory authority, irrational, or failing to consult adequately.

Strength: Flexible and applicable to government overreach.

Limitation: High threshold for proving irrationality; courts may defer to policy decisions. Applies only to secondary legislation or regulations and not primary legislation.

Rule of Law

Common law principle requiring laws to be clear, accessible, and non-arbitrary.

If digital ID legislation lacks clarity or grants excessive discretion to authorities, it could be challenged as arbitrary or unforeseeable.

Strength: Aligns with ECHR’s “in accordance with law” requirement.

Limitation: Abstract and less likely to succeed alone.

In short, and as can be seen from the above, whilst there are limited statutory and common law tools to challenge mandatory digital ID, losing the ECHR at this time would remove the most powerful and principled safeguard against it. As such, and call me a conspiracy theorist if you like, I believe that the repeated calls for leaving the ECHR are very much tied to the attempted implementation of mandatory digital ID in the form of Britcard, and that these calls for withdrawal are being made to remove possible robust challenges to Britcard under the ECHR. I do NOT think the withdrawal argument is solely about illegal immigration as claimed, considering that other measures could be taken to reduce immigration if there was political will do this.

And just to make a point, in the UK, asylum seekers (who are not yet formally recognised as refugees) are typically housed under Section 95 of the Immigration and Asylum Act 1999, which provides basic accommodation and subsistence support while their claims are processed. This is considered a humanitarian obligation. The right to such housing has nothing to do with the ECHR. The ECHR does not mandate housing and only becomes relevant indirectly in a housing-related dispute. For example Article 3 (prohibition of inhuman or degrading treatment) may be triggered if housing is dangerously inadequate. Article 8 (right to private and family life) can be used to challenge removals or evictions that interfere with family unity or dignity, and Article 6 (right to a fair hearing) may apply in decisions about housing support entitlement or appeal rights.

The 1951 Refugee Convention, along with its 1967 Protocol, both of which the UK is a signatory to, does include housing as one of the rights refugees are entitled to. Specifically, Article 21 of the Convention requires that refugees who are lawfully staying in a host country be granted housing treatment as favourable as possible, and at minimum, not less favourable than that accorded to other non-citizens in similar circumstances. However, this provision does not mandate free housing or specific types of accommodation, applies only to refugees with lawful status, not necessarily to asylum seekers whose claims are still pending and leaves room for national discretion in how housing support is provided — whether through public housing, temporary shelters, or financial assistance.

Do all of the people calling for withdrawal from the ECHR know the above points? If you challenged them about the same, would they be able to provide a comprehensive answer? I very much doubt it, and this is another reason why I feel that the ECHR withdrawal calls are not just about immigration – none of those calling for the same ever mention the detail set out above.

For your pocket book of reference the next time you hear calls to withdraw from the ECHR because of illegal immigration - notable UK Privacy and Surveillance Cases Under Article 8 ECHR

Campbell v Mirror Group Newspapers Ltd [2004] UKHL 22

The House of Lords ruled in favour of Naomi Campbell, holding that the publication of details about her drug treatment and covert photographs taken outside a Narcotics Anonymous meeting breached her Article 8 right to privacy. The judgment balanced privacy against freedom of expression under Article 10.R (on the application of Daly) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2001] UKHL 26

The House of Lords found that a blanket policy allowing prison staff to examine legally privileged correspondence in a prisoner’s absence was a disproportionate interference with the right to private life under Article 8.Peck v United Kingdom (2003) 36 EHRR 41

The European Court of Human Rights held that the disclosure and broadcast of CCTV footage showing Mr Peck shortly after a suicide attempt constituted a serious and unjustified interference with his Article 8 rights, despite the incident occurring in a public space.S and Marper v United Kingdom (2008) 48 EHRR 50

The European Court of Human Rights ruled that the indefinite retention of DNA profiles and fingerprints of individuals who had not been convicted of any crime violated Article 8. The Court found the UK’s policy to be blanket and indiscriminate.Liberty and Others v United Kingdom (2008) App no 58243/00

The Court found that the UK’s interception of external communications under the Interception of Communications Act 1985 lacked sufficient legal safeguards and foreseeability, resulting in a breach of Article 8.Big Brother Watch and Others v United Kingdom (2021) App nos 58170/13, 62322/14 & 24960/15

The Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights held that aspects of the UK’s bulk interception regime and acquisition of communications data from service providers violated Article 8 due to insufficient oversight and safeguards.

In summary

Given all I have said above, I feel confident in asserting that the immigration narrative—especially as it is being shaped and amplified by political figures and social media influencers—is being used as a crisis for a prepackaged solution: mandatory digital IDs. Just as the “Covid”narrative was leveraged to usher in the rollout of mRNA vaccines, we’re now seeing fear weaponised around immigration to mould public perception and nudge consent to tighter controls on all of us.

It’s not just the facts about immigration that are being presented—it’s the way they’re being framed. We’re being told not just what’s happening, but how we ought to feel about it. The emotional intensity, the urgency, the divisive language—it’s all part of a broader strategy that mirrors previous campaigns designed to provoke fear and compliance. The problem is real, yes,—but the manipulation behind its portrayal is what demands our scrutiny.

I therefore hope what I’ve laid out above has offered not just a clearer understanding around immigration figures, but also a balanced reflection on the calls to abandon the ECHR as a supposed solution. In an era marked by shameless deceit from power structures and politicians of every persuasion, it would be foolish to place trust in politically charged rhetoric around ECHR withdrawal. Believe me when I say that those pushing thisagenda are not just misguided—they're making a strategic play that could endanger all of us.

Immigration poses challenges—as it does for many nations. But its roots are complex and tangled in global agendas, profiteering, and business interests, much like everything else in this world. Given this, let me issue a word of caution: be careful what you wish for. If the ECHR is scrapped, don’t expect Article 10 to shield your right to free speech when the police come knocking over a social media post. And forget about invoking Article 8’s protection of privacy when digital ID systems become mandatory and inescapable. Once these rights vanish, they’re not coming back.

Until we confront and dismantle the broader “one world” agenda that’s being imposed on us all, demanding the removal of even flawed rights is not just impractical—it’s tactical self-sabotage. These rights may not be perfect, but they remain our last legal foothold against a slide into deeper control. To consent to their erosion now would therefore be to surrender the battlefield before the fight has even begun.

Thank you for reading this article, If you liked it and consider it of value, please share it and also consider subscribing to my publication

Fascinating article! I agree that the calls to leave the ECHR seem strange - the illegal immigrants could easily be stopped and removed because they are illegal! The massive amounts of legal immigrants are the real issue and nobody in power wants to stop their arrival. The idea that a digital ID card would help to stop illegal migration sounds dumb and I suspect the majority of the population know it would make no difference at all. Which is presumably why the Alternative Guys are being used to make leaving the ECHR sound necessary. If we leave we can deport all the bad people but we will need some sort of ID to prove the rest of us are good people - nothing to hide, nothing to fear (as the unimaginative like to say).

No apologies necessary for the length of the piece. For the first time on Substack I’ve contemplated printing it out to read it more thoroughly because you’ve clarified my own views on our sovereignty and the reality of working with, as opposed to rejecting aspects of our flawed legal system.

Prior to 2020 in my role as a trainer of the law that supports and protects adults and children, I applauded what I believed to be our robust protections of human rights. I could never have believed that our legal system would fail us when our rights were so dramatically violated over the threat of a respiratory infection that was of no consequence for the majority. I doubt if it will help us in the future but it’s more terrifying to contemplate removing possible protections completely.

As you rightly point out, mandatory digital ID systems are not compatable with Article 8 but I can’t help wondering if they might never be mandatory but are being introduced by stealth and we’re freely accepting significant controls on our rights and freedoms. A passport with digital eye recognition isn’t mandatory but you can’t travel if you don’t have one - my choice. Supermarket loyalty cards are the same, no card, no substantial discount on certain items - my choice. In Scotland I reluctantly sold my soul for a bus pass (called a saltire card!) for free travel - my choice. And the same for a senior railcard for a third of my fare but I entered freely into the agreement which presumable includes sharing my information. They’re all digital ID systems which I’ve agreed to and it would seem irrational to refuse them but I’m deeply uncomfortable with it.